Last week I had the pleasure of visiting the Denver Art Museum with my friend, Angela. Now, hold that thought and rewind two months ago. Two months ago I had the pleasure of visiting the Denver Art Museum on a first date. Do you sense the differing moods between the two visits just by reading these two sentences in contrast to each other? If you are thinking "yes," then congratulations--you are in fact attune to context and not without a social clue. It is true that attending a museum on a first date and attending the museum with a long-time friend will be two very different experiences. However, I highly recommend any good art museum as the perfect venue for a first date. The main reason is because compatibility between two people is exposed in some degree by your dialogue about and reaction to the artwork. But, I am not blogging here about my advice on dating. I have greater matters to attend to--matters of art. Matters that matter.

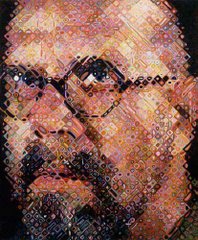

I would like to introduce you the work, Life, by Yue Minjun. (I have attached an image of the work for your reference. It is in the right hand column on my blog.) Here is an oil painting, and I apologize that I do not have exact dimensions, but my guess is that the painting occupies a space of about 15' x 9'. Each partitioned square that you see must be about 3 square feet in physical existence. In case you are having difficulties perceiving the work, I will describe the content of the painting. The subject of the painting is a wiry little Asian man with a manic, full-toothed-with-scrunched-up-nose, laughing expression. The man is pictured in each square, in a variety poses--not merely childish contortions, but seemingly strange postures, which hint at insanity or, at least, an extremely emotional state of mind.

At first blush, I blushed. (This was on the first date trip to the DAM.) I interpreted the mural sized work as representing in partitioned squares the euphoric insanity of a vulnerable human being. My Christian worldview requires me to understand humanity, and its depictions, as representative, in some capacity, of God’s image (Genesis 2:26). Only the bizarre representations of the human figure in life somehow seemed more base to me, irreverent, silly, and slightly animalistic. I was unsettled by this representation of sub-human mania, and by the fact that the guy pictured was wearing a black speedo—let me qualify this comment—the speedo didn’t bother me, nor did his nakedness, as nakedness in and of itself. I was bothered by the helpless exposure of this man, his defenselessness, both in mind and body, and the risk behind his poses.

In all honesty, I wanted to stand there pondering the oil painting much longer than I was able to. After all, I work mainly with humanity in my artwork, and this was a technically beautiful rendering of the human figure, with muscles contorted in ways not often captured by painters these days. But alas, it was a first date; I didn’t want to freak my date out by deliberating about what he might see as merely a man in a black speedo. Besides, the museum is filled to brim of interesting stimuli, so we moved on. However, I didn’t forget the mural.

Several months later, I was so grateful for Angela to suggest an outing to the museum because I had long been wondering, not only about Life, but about some other works included in the exhibition. I was thrilled to have a second chance to stand with my jaw dropped before them. You never can tell how a museum with hit you. A well curated show is worth months of brooding-over—it tides you over until the next installation. I was blessed to have Angela as my companion last Friday for many reasons, but the reason that has inspired me to blog today is that she shed reams of light on the Minjunpainting.

After escaping a rather talkative museum guard, we found ourselves in the gallery with the huge oil painting. My friend was already looking at it. I walked over and glibly said something like, “This disturbs me.” “I like it,” she replied just as quickly. Surprised, and now curious, I asked her why. Angela is a first-generation Korean. Minjun’s subject is an Asian man—not a boy, not a young man, necessarily. My friend explained that in the Asian cultures extreme emotions are always reserved, hidden, and even manic happiness is rarely displayed, especially in the case of familial patriarchs. Angela has a father and a brother, and their family is close, but she does not often witness their raw emotions. Her reflection startled me a bit, because Angie’s family has gone through so much hardship, and suddenly I imagined everything that has happened to her without the outward expression of pathos. I was shocked—this new thought in my mind quickly turned me toward a new appreciation for the painting. Angie said, “This is like the Father I never knew.” The freedom to express is what attracted her to Life.

I could no longer write off the work as another unmemorable painting, postmodern in its repetitious composition and random imagery. I had to stare at the content in light of the cultural mores, previously unknown to me, before I could feel thankful for the existence of such a strange painting. I remembered again that one reason why I love art so much is for its ability to communicate the transcendant. I think that the art that will still occupy wall space hundreds of years from now will be the art that communicates universal truth. Humanity, expression, communication—all of these elements will preserve Minjun’s painting, and I hope that you have a chance to see it some day. It would be better if you could see it with Angela, but I am not at liberty to volunteer her insights for your every museum whim. Sorry. Instead, you should bring a first-date.

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)